Day 93: Poads Road to bush campsite near road end – about 2km

*Note that the days on the trail are out of sequence between the title of this post and the titles of the previous and following posts. This is because I initially had to postpone this section due to bad weather (see posts on two previous attempts above this one). But the kilometres walked are in the correct order, to create the reading experience of a continuous north-to-south journey.

It was late December 2021, and summer was settling in. I had a week off and it looked like I’d finally be able to complete this tricky mountain section, which had eluded me twice before. It was one of the final North Island pieces remaining in my attempt to section-hike the Te Araroa Trail down the whole length of Aotearoa, north to south, as contiguously as weather and life allow. As before, I left my car at the Ōtaki Gorge road end got a lift with a transport provider, Waka, who I met via the Te Araroa trail notes.

He dropped me off at the range access point of Poads Road end, east of Levin, an hour or so’s drive north of Wellington.

He was a keen tramper too, and had asked me my plans as we drove. I’d explained how Te Araroa heads straight up to the tops from Poads Road, spends a day or so on the long ridge in the heart of the range before descending to Waitewaiwai Hut, then follows a river valley out to Ōtaki Gorge Road. He looked at me, surprised.

“In this weather? It’s going to be perfect for the tops. Do you know how rare that is in the Tararua? Instead of a day up there, you could have three or four. Why don’t you just stay on the main range the whole way?”

The main range: I’d heard of this legendary Tararua route. It describes simply walking along the tussocky tops of the longest, most central and straightest of the Tararua complex’s several long, ragged ridges. I told Waka I supposed the Te Araroa Trust prefers to send trampers out via the lower Waitewaewae route to lessen their exposure to sudden bad weather, which can be literally a killer if you get trapped on the tops. He shrugged, unconvinced. But the exchange did make me think.

There’s an info panel at the road end with a 3-D image of this whole southern part of the Tararua park; I ran my fingertip right along the long, sinewy, golden ridgeline, from the Dundas ridge in the north (near Eketāhuna) to the Southern Crossing in the south (near Upper Hutt). It looked like a sublime, secluded, wild highway, exclusively for those walking single file. It was definitely tempting.

So far though I’ve been totally faithful to the Te Araroa route that’s been carefully planned and built up over decades, hard-won by much negotiation with landowners and other stakeholders. It’s become a kind of pilgrimmage route, and not one I’d deviate from lightly. It feels like cheating. Like a short-cut.

Yet I wouldn’t be, really. If I took the alternate route along the main range, I’d actually be walking further than the official TA route – while still walking roughly parallel to it.

I decided to mull it over as I tramped.

A quick skip across now-familiar paddocks and I was in the welcoming forest. Within a minute or so I passed the turn-off for the old Te Araroa route up to Waiopehu Hut. (Te Araroa no longer uses this route, preferring the shorter Gable End one, but I did it on an earlier attempt as Gable End was blocked by a slip.) The night wasn’t far off so I found a flat spot near a creek and settled in for the night, ready for an early start in the morning.

Day 94: Campsite near Poads Road end to Te Matawai Hut – about 10 km

I had a long day to get up to my next stop: Te Matawai hut, right up on the bushline, some 700 metres’ climb – through terrain I’d already crossed on my way down from that previous attempt. So I wasted no time breaking camp. It was still fairly early by the time I was swinging along the easy, mostly flat track, with views through sunlit bush down to the Ōhau River.

Soon I was at a the big slip that had impeded me on my last attempt at this section – I’d decided then against risking a scamble across the steep washout, from which a false step could easily send you tumbling into the Ōhau. It had added several hours to my trip after I had to double back and go up the alternative route, via Waipoehu. Being midsummer this time, the slip was dryer and had less loose, muddy material on it, but it still looked imposing.

This time, though, there were two supports to get across: first, a steep track has been cut up and around the slip. Secondly, someone has knotted a fairly sturdy line from an anchor point, letting you scramble across with relative safety. I took the latter option, since it looked quicker and easier. It was still a wee bit hairy, but not too bad.

In minutes I was past the turn-off to Six Discs Track (which also goes to Waiopehu) and over the swing bridge leading to the South Ōhau campsite. I scrambled down under the bridge into the Blackwater Creek to fill up my bottles. There’d be no more water until Te Matawai Hut, a good six or eight hours of climbing ahead. Here’s the bridge seen from the creek:

Then I was grinding up Gable End track, steep and tough. Last time I was here I was coming the other way, swinging down from the snowy tops in the near-dark. I was struck both times by the exuberance of this particular stretch of bush. How the trees crowd up out of the ground. How the body of a fallen behemoth seems to have barely hit the leaf litter before getting swamped by upstart saplings:

The epiphytes, too, are impressive – great vertical carpets of them:

The mud is as relentless as the vegetation and the gradient:

But, on all sides, there are small and perfect consolations.

Mostly through low bush, with occasional open stretches, I made my way over Mayo Knob (666m), Gable End (903m) and Richards Knob (985m, named for a tramper killed nearby on an expedition.) Then it was the pain of losing quite a lot of that hard-won height heading down into Butcher Saddle (690m). Only to have to slog laboriously back up on the other side.

It was heavy going, lugging several litres of water and a week’s worth of food up the range. Especially over ground I’d already covered. But I kept grinding and right on nightfall made it to Te Matawai Hut (900m). The winter before I’d spent one of the coldest nights of my life in this cute little shelter, before bad weather forced me to pull the plug on that attempt.

I ate my noodles and perused the hut book to get an idea of what lay ahead. “Deep tussock plus deep mud = dead inside”, one tramper tersely noted.

I took a pensive sip of peppermint tea and turned to a tramping club’s annual mag. “Do you know why you tramp? You’ll say it’s for the views or the company. But in fact, neither can be counted on. I know why you really tramp. It’s because you like suffering.”

On that note I turned in early, ready for the painful delights ahead.

Day 95: Te Matawai Hut to Dracophyllum Hut, 8.5km

It was a damp, chilly morning, the last of a stretch of bad weather before a forecast long stint of golden days. As I climbed up the narrowing ridge from Te Matawai toward the main range, sunlight found its way more and more through low cloud.

It’s a steep pinch up to Pukematawai (1432m), and often razor-backed. I was glad I hadn’t tried to tackle it the year before, when it had been under thick snow.

There was an icy breeze at the top so I hunkered down for lunch on the lee side, with a view past wildflowers down into Park Valley.

A quick detour through clag to the top of Pukematawai yielded no clear view of nearby Arete, a well-known peak I’ve seen from afar but never up close. In fact, there was no clear view of anything. So I was soon heading south again along a very up-and-down ridgeline.

This sort of tramping is pretty brutal – you’re constantly going either steeply up or steeply down over slippery, uneven ground and it’s hard to find a ground-covering rhythm. Being a section-hiker, rather than doing the whole length of the country in one hit, means you have to start from scratch on your trail fitness each time. So I was soon feeling pretty battered. But Butcher Knob (1158m) loomed through the mist, making a good target:

After that the track goes in and out of low alpine bush, with some great views as the cloud lifted, across the Horowhenua plains to the Tasman Sea in the east. That orange dot in the foreground is Te Matawai Hut:

The ups and downs just kept coming. It was a long afternoon:

Some consolation was in the continuing, sweeping views down into Park Valley, a fabled landmark, route and playground I’ve often heard of but never, as far as I can remember, gazed upon:

Mounts Nicholls and Crawford, the next day’s destination, slowly emerged in the distance. I love this aspect of tramping – how by dint of constant, arduous effort, the land slowly unfurls in front of you.

Finally I reached Dracophyllum Hut, cosily nestled at about 1100m in goblin forest. I was delighted to find I had this sweet little two-bunker all to myself for New Year’s Eve.

Or so I thought, until a lean and steely looking figure came loping out of the twilight. But he was only stopping for water, it turned out – he was running a totally insane, long-distance route called the S-K Traverse. He told me about it while he rehydrated and I eyed his tiny pack, containing only an ultralight stove, wet-weather gear, thermals, a sleeping bag and some dehydrated food. S-K is about 80km, goes down the whole of the Tararua Main Range and stands for Schormann to Kaitoke. The starting point is named after a now-defunct track up from Putara Road near Eketāhuna in north Wairarapa, and it ends at Kaitoke, near Upper Hutt.

It’s become a legendary route that people complete in 24 hours: to me, a barely believable feat. But it’s a thing.

This guy had started running early that morning, would bunk down in Nicholls that night (he was aiming to be there by 10pm or so), then run out to Kaitoke on New Years Day. In two days, he was covering what would have taken me, at my usual stately pace, a solid week. He shrugged gently at my amazement, and with a flash of teeth and heels was gone into the evening.

Still shaking my head, I hung up my gear, wet from camping out the first night, in the last of the sun.

I got myself set up inside before heading up to the hilltop just above the hut to take in the last sunset of the year. It’s really a neat little whare.

From the top of Dracophyllum Knob (1117m) I took in the mountains all around, golden in the last rays of 2021. To the north were Pukematawai and Arete; to my east, Carkeek Ridge including the peaks of Thompson (1448m) and Lancaster (1504m).

To the south-west, the sun went down in splendour above Cook Strait.

Thick cloud slowly filled the strait and the valleys and plains. Beyond on the horizon, back-lit in rosy hues, were the hills around the Marlborough Sounds. Next to me, the harakeke shone.

Here’s my route ahead the next day, along the main range toward Mt Crawford, which is capped in wispy cloud.

Watching rose turn gold on the last evening of what had been a heck of year, I thought about the people dear to me, and their links to places dear to me. That lead me to thinking about the original people of this special place, and their ongoing links to it as owners, guardians, users and travellers. All the sunsets and centuries they have seen go by from vantage points just like this. Who graciously allow trampers access. Who guard all this beauty and who have known it deepest and longest: Te Atiawa, Te Atiawa ki Whakarongotai, Ngāti Toa Rangatira, Muaūpoko, Ngāti Raukawa, Taranaki Whānui ki te Ūpoko o te Ika, Ngāti Rangitāne and Ngāti Kahungungu.

I’d lugged in a hipflask, and with a wee dram I toasted them, and the last of the sun.

Day 96: Dracophyllum Hut to Nicholls Hut, 5km

That kilometre count for the day doesn’t sound like much, but given that most of it was either steeply up or steeply down, it was a long, tough day.

The morning sky was clear and hard, promising heat. Behind me, Arete peered over Pukematawai’s shoulder, watching me go.

To the east, the Broken Axe pinnacles between Jumbo and the Three Kings, a hair-raising but exhilarating route I did by myself a few years ago:

The route ahead – a long, forested ridge leading up to Nicholls and Crawford:

But first, I had to go over several obstinately steep and unrelenting “bumps”. This prosaic tramping term conceals a sweaty reality, involving scrambling down, and then back up, then down, ad infinitum. It’s a type of tramping that can feel very Sisyphean. Here’s the first of these awkward but spectacular bumps, Puketoro (1152m):

Then it was over the shoulder of another rough old bump, Kelleher (1182m), with a quick detour to its summit. Then down and along the long bushy ridge, and a long grunt up, up, up onto Nicholls. That’s where I took this next shot, looking back the way I’d come over the past two days, all the way to Pukematawai on the horizon (to the right). To the left, just beyond the bushy ridge, is Kelleher.

I’d got away early and felt like I’d already had been a long, hot, hard day, but it was still only mid-afternoon. Below was Nicholls Hut. I had time to carry on over Crawford, but I was out of water and there was none on this sun-baked ridge. Down to Nicholls and its rainwater tank I went.

As you can see in the foreground of the pic above, Nicholls is securely tucked in a sheltered valley, with stunning views eastwards down the Waiohine River valley to the Wairarapa and the Aorangi Range. A gem of a hut.

It looks onto one particularly striking, craggy face – McGregor, I think:

Around the water tank, a stunning crowd of flies milled in their thousands. Inside, it was cooler, still and quiet. I lay on the bank and rehydrated, watching the sun slowly move down the mountains. To stay, or carry on? I was dried out, bone-weary and not very trail fit, and too tired to decide. I dozed off.

When I woke up I still had daylight left. What to do? It was a hard decision. I had to get out to the Ōtaki Gorge road-end in time to get to work, three days hence. I had a long window of perfect weather and a detour along the main range beckoned. But would I have the energy, not to mention the time? I lay there and drank water and considered.

Normally I don’t like deviating off the Te Araroa standard route, but this would be a noble exception.

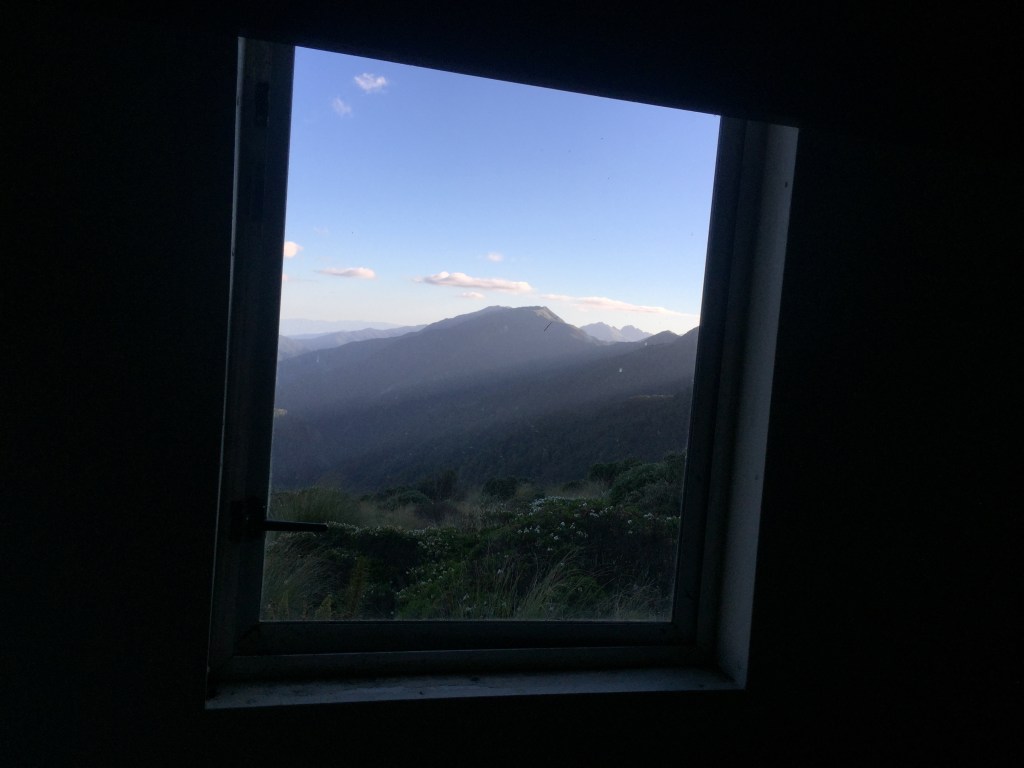

The day had taken a toll. I decided to sleep on it. All evening through the hut window I could see the main range’s most famous highlight, the legendary Tararua Peaks, beckoning me. They’re the lighter coloured twin peaks on the right of the bigger, darker peak in the centre of the window – Aopkaparangi, I think.

Beyond, below the setting sun, lies the Aorangi Range in southern Wairarapa.

All night as I slept, those near-vertical, legendary peaks swayed in and out of my dreams.

Day 97: Nicholls Hut to campsite on Aokaparangi, about 11 km

In the morning I still couldn’t decide. Alternate routes are a thing in the long-distance hiking community – not sticking slavishly to an established route if there’s another way that offers something special. But for me, sticking to a carefully crafted and curated trail has a certain charm. As if Te Araroa is a latter-day Camino de Santiago.

But then – even the Camino has alternates. Over the centuries different ways to reach the same objective evolve, each with their respective stories and traditions.

I’d resisted alternates for the whole journey so far, all the way from Cape Rēinga. But this main range opportunity seemed too good to pass up. You simply can’t do it in in poor weather – too dangerous – and I had a window of the most perfect weather imaginable.

However, I risked being late for work if I went the longer way. And I hate rushing in the back country. I’d decide on top of Crawford, I thought. I said goodbye to the thronging flies and to the otherwise peaceful shelter of Nicholls Hut:

Once over the shoulder of Nicholls it was an often-thrilling , steep and narrow causeway up toward the top of Crawford. It was another banger of a morning and the views were immense. Here’s Mt Ruapehu, with a white flash of snow or cloud or both, on the horizon. This is looking north, beyond Oriwa Ridge and over a slice of Tasman Sea:

And here’s the route up the side of Crawford, the summit in the centre:

To my south-west, Kāpiti Island, with the Marlborough Sounds and Tasman Bay beyond:

The next pic, below, is from near the summit of Crawford (1462m), looking south-east, along the main range. It shows the alternate route I was contemplating.

From here that route goes down past Junction Knob (1375m), past Anderson Memorial Hut, then along that exposed, high ridge over Kahiwiroa peak (1320m) and Aokaparangi peak (1354m) to Maungahuka Hut and peak, and on.

The standard Te Araroa route, meanwhile, heads off Crawford here via Junction Knob and Shoulder Knob, down to Waitewaewae Hut, then runs along a couple of valleys roughly parallel with the main range, out to Ōtaki Forks. Easier, quicker, but could I bear wasting such a spectacular opportunity for tops travel?

I stood at the signpost at the fork in the path on Junction Knob and thought it over one last time.

All those open, clean, tussocky tops beckoned.

It was too good a chance.

I took the path less travelled by.

I made it to snug little Anderson Memorial Hut in time for a late lunch.

Then it was back into bush along a low ridge, before another slog, this time up onto the golden, tawny flanks of Kahiwiroa. The main range route was unspooling in all its grandeur now, like some kind of private suspended path between the sky and the earth. A long, high lane:

From a distance these rugged peaks with their savoury, mouth-filling names look soft-shouldered, easy. The ridge-line route appeals as a tussocky staircase or even escalator. But up close the reality of the likes of Kahiwiroa is gnarlier:

The long summer day was drawing in, and Aokaparangi was still a dauntingly long way off:

It was hairy at times. This next shot is taken looking straight down the side of a razor-back ridge:

Finally I was on the final, steep approach. There’s a hut below the summit of Aokaparangi and the long, warm twilight would get me there before dark.

But that ridge just seemed to go on and on, refusing to submit to my stride.

Finally I neared the junction where a spur goes down to the hut.

I was footsore and dehydrated but I’d made it. It’s a wonderful spot for a hut, right on the bushline in a remote, silent, magnificent place, a good two days’ walk from any road. As I drew near, though, I heard voices and my heart sank. It’s only a two-bunker and I could already tell they were both taken.

The couple with two kids in occupation were really nice though, chatting to me as I filled up with water from the hut’s tank and helping me find this nearby, pristine camping spot. Hard to complain, in the end:

I ate my noodles and drank my liquorice tea and watched this glorious carry-on:

Day 98: Aokaparangi campsite to Kime Hut, about 11.5 km

Over breakfast, I watched the dawn light shine on the Pacific. It was enough to drown out all manner of aching bones.

On the map, and from the peak of Aokaparangi, the route to Maungahuka looked straightforward. A nice, clear ridgeline, like a steepish hallway you’d saunter up. I’ll just bowl along to Maungahuka for morning smoko at the latest, then along to Kime for a late lunch, I thought. But the path was full of those infamous Tararua bumps, including two actual, named peaks which I’d completely overlooked – Wright (1196m) and Simpson (1174m). And in the way of these things, each of them involved a painful, slow, precarious slog up, then an equally tough slog down, then up again, and so on. Marvellous to look at and tramp among but, but saunter over them? Smash them out before morning tea? Yeah, nah:

But man, was it a spectacular morning to be alive, and out in the back country, picking my way along the high spine of the land:

Finally I was on the last, tough, narrow ascent to Maungahuka. Over its right shoulder, those sheer and storied Tararua Peaks. Just looking at their near vertical sides made my heart hammer faster than it already was. I realised I’d have to reconsider my hope of getting out to Ōtaki Gorge Road by that evening. There’d be no hurrying over these puppies:

Finally, Maungahuka Hut came into view. It’s one of the most picturesque hut sites I’ve visited:

Maungahuka comes from maunga, meaning mountain, and huka meaning snow, and this whole range is often blanketed in white through the middle part of the year (and beyond). Today though it was sunlight falling hard and heavy, and it was a relief to skirt the tarn and enter the hut’s cool shadow. Even there, the view and setting were among the best you’ll see:

I filled up with water, food and coffee and tried to compose myself. The Tararua Peaks were just ahead, and I had just realised I was unusually nervous. I could feel my pulse beating faster than it should when you’re at rest, sipping coffee before a majestic, silent, sun-soaked panorama. I reflected on why. Sure, the near-vertical rock columns are famous for being a bit scary: they used to be only passable by those with high levels of daring and mountaineering skills, as well as ropes. Then the Forest Service put in a chain ladder, later upgraded by DOC to the current heavy-duty, 70-rung, seismic-tested steel ladder bolted to rock. But it’s still much respected as a particularly hairy little section. Which, normally, would have exhilarated rather than bothered me. So what was different?

Something I haven’t mentioned until now is that at that point, my partner and I were expecting our first child. Since then my son has been born, and he’s an utter delight. But at that moment, I was suddenly conscious of what it would be like for him to lose his dad before even drawing breath. It put risk-taking and danger into an entirely new light.

There was nothing for it though, except to calm down, put one foot after the other, and make my way carefully toward my future son. Step by step, through the narrow little notch between Tunui (1325m) and it’s slightly smaller partner, Tuiti.

First though there was a last look back at the rugged, lofty lane I’d been following those last few days. That’s Simpson in the foreground, then Aokaparangi, then Kahiwiroa, then Crawford poking up near the centre, and Pukematawai on the horizon.

Here’s my first close-up view of Tunui:

Already the footing was getting a little precarious as the spine of the land narrowed. It’s not only the difficult terrain that gives this place an aura. To the iwi of the area, this is a crux of many ancestral stories and territories. Te Ara notes, for example, the Ngāti Toa people named this whole range Te Tuarātapu-o-Te Rangihaeata (the sacred back of Te Rangihaeata, a Ngāti Toa leader) to seal a peace deal between Ngāti Toa and neighbouring Ngāti Kahungunu. Here, at this knotty, rocky junction, it felt as if I was right between those gigantic shoulder blades.

The going here is tough, and you have to reflect minutely and humbly on the land as you traverse it, often on all fours – every foot-fall or knee-press counts, every hand hold.

Close to the steepest part, chains are bolted into the rock. They were mostly unnecessary for me that day (except for psychological comfort), but in ice, snow, rain and fog they would be a godsend.

Finally it came into view, the fabled ladder.

I used to live in Wairarapa and from certain points there you can see these distinctive twin peaks jutting up, like remote rock chimneys. I’d been watching them for years. Reading and hearing about their history, about others’ adventures on them. Now I was sidling right up to them.

At the ladder’s foot I laid down my pack to have a breather. It was a moment to savour.

At the top of the ladder, framed by the two outcrops I stood between, the views were a marvel. I was in the heart of the Tararua Range, just as about as far from a road-end as you can get in this park. The bush far below was silent, serene. The tussock rippled, languid, lapped by the breeze.

It wasn’t over, though. More scrambling and dangling and scrabbling lay in wait.

The next pic shows, from the top of Tuiti, the route ahead. That moment, again, when you crest a hill and a new swathe of tramping unfurls before you. The peak in the foreground is McIntosh (1286m). On the horizon, two peaks of the famous Southern Crossing, from west to east, Ōtaki to Upper Hutt: Bridge Peak (1421m) and Mt Hector (1529m). The destination I needed to reach by nightfall, Kime Hut, was between those two peaks. Till then, I’d have no opportunity to get more water and no respite from hard, undulating tramping, mostly upward. It seemed very far away.

Looking in the other direction, Tunui in the foreground, and the way I’d come spreading out behind.

In huge landscapes like this it’s easy to overlook the tinier delights:

You can’t look at them too closely though, because you have to keep your eye on the often-dicey footing:

Somewhere up around the top of McIntosh I was really struggling. My feet were in a bad way, blistered, swollen and sore. It’s a given when you haven’t done a lot of training, and then head out into the back country and walk all day for nearly five days straight. Sooner or later your feet will say: we need a day off.

But that wasn’t an option so I just had to nurse those battered little hobbit hooves along. That meant stopping every hour or so, shedding boots and socks, attending to blisters and crushed toes, and putting my feet up on my pack for fifteen minutes. It made for a long, hot afternoon, especially as there are no trees on the high tops, and therefore no shade. It was midsummer, roasting hot, and I was sunburned, dehydrated and running out of water. But there’d be no more till I got to Kime, still a good four km and 300m climb away.

At one point I curled up under a gnarled and woody shrub, blasted bone-white and low to the ground by the prevailing northerly, nearly bare of leaves. It was the only meagre shade I could find. Despite the pressure to keep going before the light faded, I couldn’t keep from snoozing a little.

Finally, the sun began to fall, the sizzle to go out of the air and the shadows to lengthen. A deceptively tough scramble got me up and over McIntosh and then Yeates (1205m). Then I was looking back toward the twin peaks, and beyond them Maungahuka and Aokaparangi:

With much swearing, sweat and foot-soreness I continued then over Vosseler (1108m) and Boyd-Wilson Knob (1138m). To give myself some attacking energy I began personifying the last one as a kind of mean, posh bully: “that Boyd-Wilson knob”. Finally I was on the last, long, tough ascent, up a steep spur onto the east-west range that forms the T-junction terminus of the main range. Here’s the view back the way I’d come from that point, from near Bridge Peak. You can see lights coming on down on the Wairarapa plain:

Then it was a slog in the gathering gloom over Hut Mound (1440m) to Kime Hut. On the way, the lights of Wellington winked around the harbour in the distance:

After what seemed an unfeasibly long time I was stumbling wearily onto Kime’s ample verandah and slipping into the shadowy interior. On several bunks were the still forms of other trampers, already asleep. I got carefully into my sleeping bag in the dark, every fibre aching. I munched biltong, sculled water and sipped whiskey. It had been a mammoth day but I’d made it.

Day 99: Kime Hut to Ōtaki Gorge carpark, about 12 km

In the morning I had a good and much-needed sleep in, ear plugs and eye-mask keeping me drowsing through the other trampers’ morning clatter. When I finally got up I felt like I’d been hit by a truck. I’d reached my physical limit, the most hard tramping I can really do at this stage of my life without a day off: five days’ hard, continuous walking. I really needed a break but there was no way – I had to get back to Wellington for work. Slowly I put myself back together, breakfasted and set off. Below is the view looking back at Kime Hut, out toward Hutt Valley and the Remutaka Range. Looks like I was too tired to focus properly:

To the north, Mt Ruapehu trailed a plume of cloud, beyond Bridge Peak and the Oriwa Ridge:

From Dennan (1214m) the ground dropped away like a rough staircase down toward Field Hut. In the distance, the Ōtaki River ran down to the Tasman Sea:

The next pic is looking back up toward Dennan, from around Table Top (1047m). It looks benign in this kind of weather, but if you’re heading the opposite way to what I was, i.e. up onto the exposed tops, this is a possible point of no return. More than one tramper has decided to push on from here despite a bad forecast, and never made it home. The Southern Crossing is notorious for offering few escape routes when the weather turns savage, which it can do in a blink. Table Top is a good place to take stock.

For me though, it was down into the cool relief of the bushline. It was the first time I’d been under a canopy for days.

Around the point I heard a hectic crashing near the track which made me stop, heart pounding. But only for a moment – in Aotearoa that sort of sound can only be something much more keen to get away from you than harm you, like deer, pigs or stock.

I pushed on and soon reached the quirky, old-school charms of Field Hut.

It’s a comfy, historic hut full of character, and at only a few hours from the road-end, an easy overnight destination. Someone had left a partly complete jiogsaw puzzle on the table.

There’s a sleeping platform downstairs, near the log burner, and upstairs there’s a neat loft with plenty more room:

Historic photos show the hard work needed to build and maintain this old beauty:

It’s a special place: one of the first purpose-built tramping huts in Aotearoa, and the oldest surviving recreational hut in the Tararua Ranges. The foundations and framing were built with pit-sawn timber from trees felled nearby, and the rest of the materials were hauled in by packhorse. It was built in 1924 by members of the country’s first tramping club, and arguably the people who invented the term tramping: the Tararaua Tramping Club. Here’s one of its founders, Fred Vosseler, in the hut named after his friend and co-founder, Willie Fields:

Someone’s note in the hut book confirmed what I’d thought about the heavy crashing through the scrub up near the bushline: wild goats are known to roam there.

Then it was on and down the long and snaking path, with the obligatory hourly stops to let the tears drain out of my crying feet:

Finally the tranquil river flats at Ōtaki Forks opened up through the thinning bush.

The path wends down through abandoned paddocks of long grass. In one, under a canopy of mānuka, I found this amazingly filigreed creature:

It was dead, the enormous frame a near weightless husk. Wikipedia tells me it was probably Uropetala carovei (New Zealand bush giant dragonfly). Their Māori name, kapokapowai, means “water snatcher”, for the extendable jaw that shoots out to snatch prey.

I pushed on, past the turnoff to Pārāwai Lodge (where I’d spent a night on an earlier Te Araroa expedition) and across the swing bridge to the gravelled Ōtaki Gorge Road. There’s a turn-off a few kms along it to a lengthy bypass around a big slip. Several locals and other trampers had told me the slip is safe to cross on foot, if you’re careful. I was pressed for time and didn’t fancy a two- or three-hour, steep and slippery bypass, so I nipped across. It’s an impressive slump of mountainside, and you are perched at times a little precariously above the river. But there’s a well-trodden path across, someone’s rigged up a helpful hand-line, and it was much quicker and easier than going around.

Note: The Te Araroa website’s “trail status” page is currently showing that a safe path across the slip has has constructed. I’d recommend taking it, in preference to the steep, much longer by-pass, which is still in place.

Finally I was at the Shields Flat Carpark, where I’d left my wheels. This is looking back at the gate I’d just scrambled over, as the long summer dusk closed in.

That was it – I’d done it. The whole North Island between Waikato and Wellington, all-but complete. (I’d completed Ōtaki Forks to Wellington earlier, when bad weather forced me to skip ahead, against my normal policy of completing each section consecutively. My account of that section follows this). Most of Auckland and all of Northland are done, too.

Still to walk: A three-day section of the Hunua Range, south of Auckland (closed due to kauri dieback – if they don’t reopen it by the time I’m ready to tick it off, I’ll walk the road by-pass); one kilometre of Te Kūiti main street (skipped because the person I was staying with insisted on dropping me off further down the road than I wanted); and the last day of the North Island, between the Wellington suburbs of Ngaio and Island Bay. Which I’m saving up for when everything else is done, so that when I walk down and touch the water of Island Bay, I’ll know that I’ve walked every last bit of land between it and Cape Rēinga.

But apart from that, I’ve walked every metre. It’s a very good feeling.

Now that my son Maian has arrived, those final North Island Te Araroa tramps – and the whole of Te Waipounamu/ the South Island – will have to wait. Possibly until he’s old enough to join me.

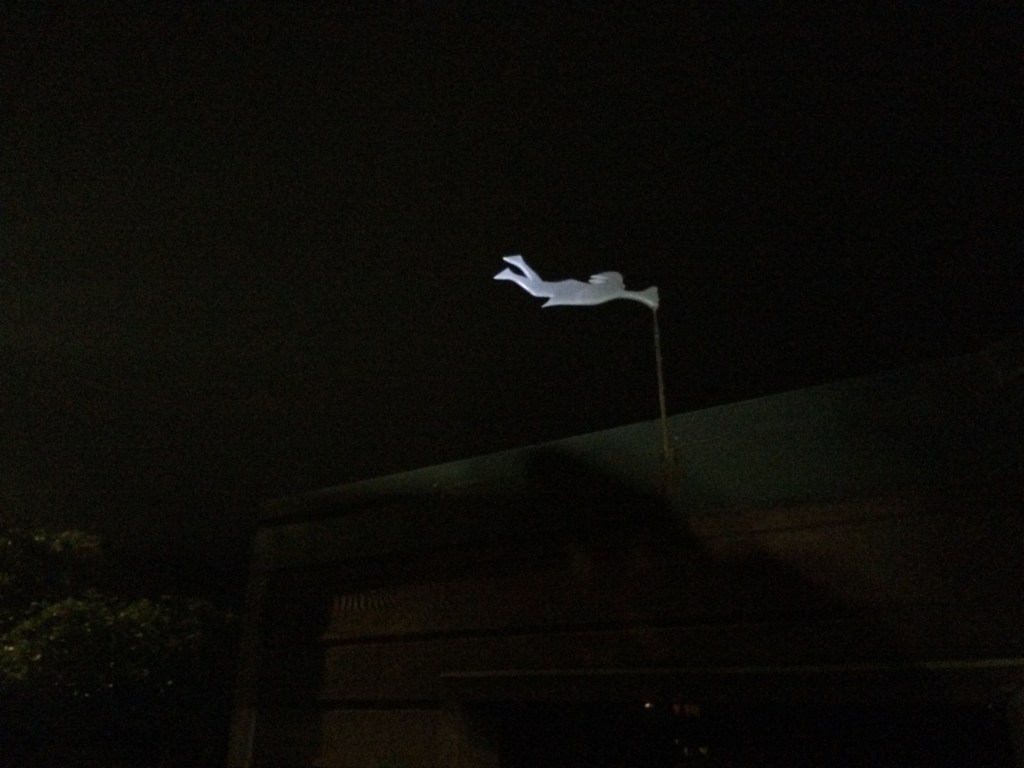

On that note, here’s a picture painted to welcome Maian into the world, by my friend Chris Murray’s daughter Olivia:

When that time comes, I’ll put an account of it on here.

Thanks for reading my Te Araroa journey so far. Previous legs of it are posted above this one, and as mentioned another few posts follow, covering the path to Wellington.

I’ll conclude this long chapter of tramping and blogging with a whakataukī (Māori proverb) that’s stood me in good stead these 99 days (spread over five years between January 2017 and January 2022) and 1500-odd kilometres, from Cape Rēinga to Pōneke:

Whāia te iti kahurangi, ki te tuohu koe, me he maunga teitei.

Seek the treasure that you value most dearly, and if you bow your head, let it be to a lofty mountain.